The King and I

My father followed pro sports as if it were his job. In fact, he often didn't have a job, but income not with standing, he had season tickets to the Phillies, Sixers, Flyers, Eagles. He was a fanatic. My childhood memories of time with my dad include watching him shave—I was afraid of how the shaving cream transformed him--doing errands with him on Saturday mornings—he kept Archway cookies underneath the seat of his car—raisin, which I detested--and driving into Philadelphia, holding Daddy’s hand as we made our way to our seats. I’d try to understand whichever game I was watching, while Dad, listening to his transistor radio, juggled food and his stats sheets and pretty much ignored me. They were odd evenings. I remember being cold at football, overwhelmed by noise in arenas, tired at baseball. By high school, I had stopped going. I never went to a football game in college and never felt I'd missed out.

The man I married, a mid-westerner raised in Ann Arbor, follows both college and pro basketball and watches football if Michigan is playing. His interest in basketball meant I could sit near him on our fold-out futon in our NYC apartment; I liked how fast moving the sport was, how watching it on TV made it easier to see the plays. In the 1990’s, we’d watch the Bulls. I liked Scottie Pippen’s face, was interested in what outrageous thing Dennis Rodman might do next and what color his hair would be.

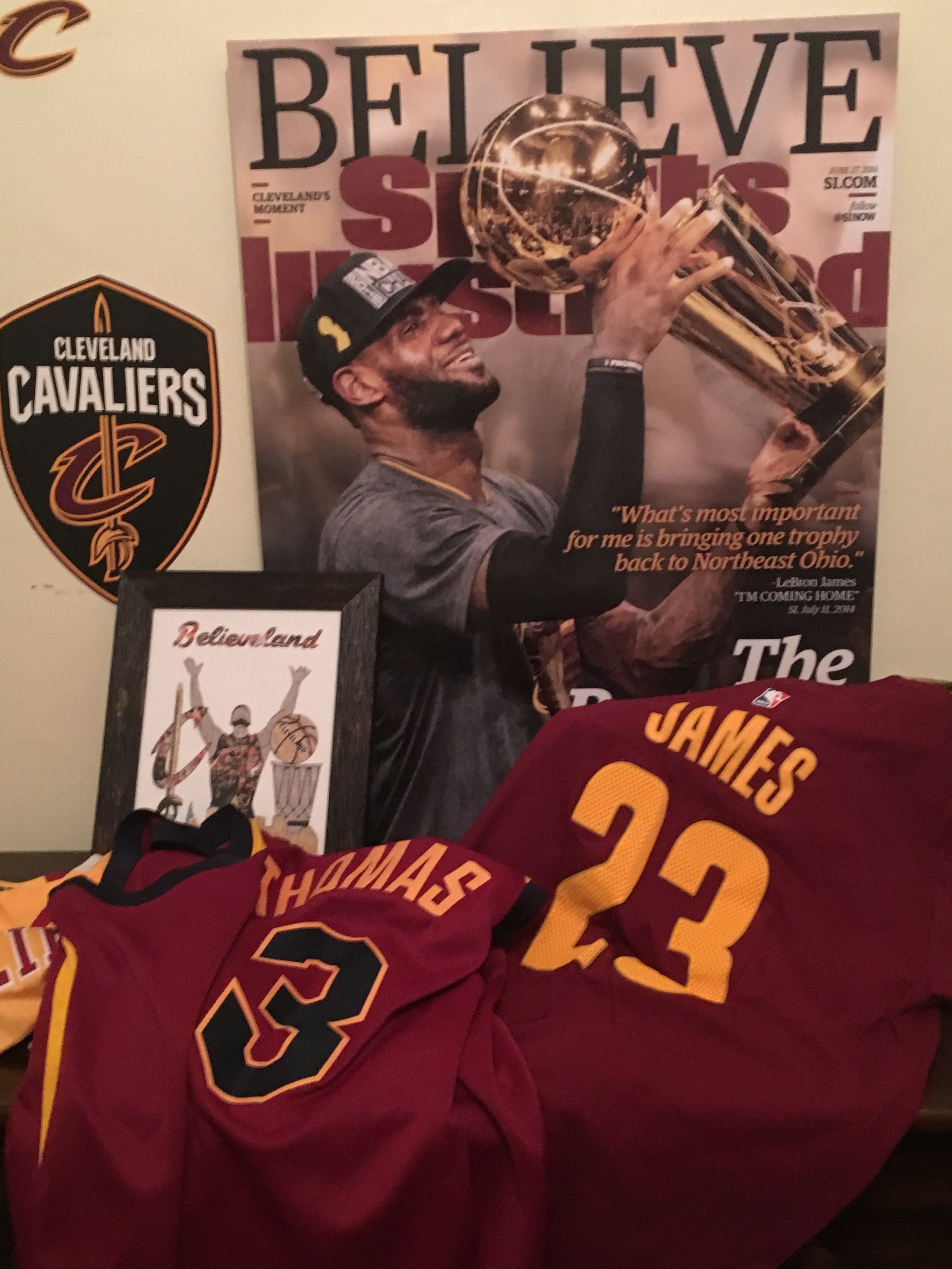

Now, our son, thirteen, is a Clevelander and one obsessed with basketball. For the past several years, he has hung out with the older girls on the basketball at the school I lead. He played briefly on his own school’s intramural team, but preferred practicing with the high school girls at my school. This past year, he was promoted to Manager. In spending several hours a day with our team—from November to March—he learned the game. He and his dad watch basketball on TV. The two of them go to games, enjoying a male camaraderie unusual in our female-dominated family on the campus of an all girls’ school. He acquired Cavs jerseys; he gave Cavs jerseys to his sisters one Christmas. He made a Cavs shrine in his bedroom with photos of LeBron and Kyrie. These days, dressed in Cavs pajama bottoms, he plays a basketball game continuously on his Switch called NBA2K18. He watches a funny web series called Game of Zones on his phone. He quotes stats and trivia about the players, about other players and other teams. A few weeks ago, we bought a hoop, and my husband put it up outside in the school parking lot, so our son could shoot baskets in the evenings and on weekends. He is not yet as tall as he wants to be, but he is determined. I wish he had really known my dad, who died when Atticus was only five. I think about the pleasure my dad might have taken in a grandson who loved sports.

As I write, it’s Game One of the NBA finals. The game’s end will be a heartbreaker, but I don’t know that yet. LeBron James, the King, forward of the Cleveland Cavaliers, is on the floor, bonked into by Draymond Green. My son, transfixed, is muttering, “I knew it,” in private conversation with the commentators as they ponder the foul against LeBron. Basketball thrums, the background to my life as the mother of this son. He is knowledgeable. He is loyal. He is interested. Because it matters to him, my own interest has perked up. I know the players’ names now; I ask questions, which my boy answers. How old are they? Where did they grow up? I feel a surge of pride when the Cavs take the lead, a clench of misery when we give up the ball or when Steph Curry shoots and scores a three at the end of the first quarter. Basketball is part of the rhythm of my daily life—at least post-season.

Two years ago, when we won the championship against our nemesis, the Golden State Warriors, I was in California at a meeting. In enemy territory, I felt both jubilant and lonely. No one else was happy that the former steel town we call home had enticed the King to return to his roots to win an NBA championship for us. Victory is sweet—and it doesn’t happen all that often in our city. We cling to hope. This year, there are rumors that LeBron will leave again if the Cavs don’t clinch another championship. The team got rebuilt mid-season, and there has been a lot of grumbling. People don’t seem to like the coach. Everyone’s a critic. Billboards on the highway proclaim that the Sixers want LeBron. “Don’t leave us again,” I whimper to myself. “We need you. Our whole region needs you. My son needs you.” I love the huge black and white photo of LeBron that is painted on a building down town, arms spread, clapping up the dust, so his hands don’t lose the ball, 23 blazing. I like that he is a symbol of hope and possibility and dreams that come true.

But what if we can’t beat the Warriors in this series? What will happen to us? And when did I begin to include myself in the collective WE of the Cleveland Cavaliers? I worry, sometimes, that LeBron plays alone too much, that he comes alive in the third quarter, that he should pass more, but he also awes me. He’s remarkable. His wingspan dazzles. I watch his face, try to read his expressions when the camera zooms in. When one of my students spent weeks in a local hospital rehabilitation center last fall, we hung out in the Cavs lounge—sometimes I wondered if they might show up. I was sad when Kyrie left the team. I marvel at J.R.’s tattoos—and now I’m fretting that the team won’t forgive him because of what happened in the last seconds of that first game. I’m glad Kevin Love has completed his concussion protocol. I like Larry Nance, Jr. because I listened to his sister coach a team my girls played against, and she was kind and tough and tall and had a beautiful speaking voice. LeBron’s kids go to a nearby private school. I hear he is a great dad. I find myself hoping his son will go to my son’s school for high school—if so, maybe I could meet the King.

I struggle with the fact that Steph Curry, point guard for the Warriors, is a great ballplayer. My husband reminds me of this fact fairly often, but it feels disloyal to acknowledge his prowess. Because he was born in Akron, I want him to be on our side. Imagine if he and LeBron both played for the Cavs. My husband explains it doesn’t work that way. I hate how Steph’s mouth guard hangs from his lip, hate that he sinks every shot he takes, hate that he is as good for his team as LeBron is for ours, hate that he must be pretty smart because he went to Davidson, hate that I can’t just hate him purely…Then I shake my head at myself. LeBron and Steph are celebrity athletes, demi-gods. I have relationship with either one of them, no reason to spend so much time thinking about them. I know almost nothing about basketball. But I love watching my son watch the games, love the times I have seen him, dancing crazily, on the Jumbo Tron at the Q, thrilled to be part of something larger than himself. Is that what hooked my dad? Referred glory? Maybe.

To my astonishment, somewhere along the line, I have become a fan. I hope my dad is watching. Maybe not, though. In my mind, cheering for our home team is required. The Sixers are yesterday’s team, Dad. Whatever it takes, we Cavs fans are all in.