“Do you want that stone?” my sister asked on the telephone.

“Which stone?”

“The carriage block that used to be at Midland Avenue. The one with KLOTZ engraved in it.”

“Oh, yeah. Yes, I think I want it.”

“Okay, I’ll take it to Eagles Mere.” She hung up, efficient.

My sister was selling her home in Delaware, so she would schlep the stone to the summer house we owned together.

Why did my father’s family have a carriage stone engraved with our surname, anyway? It seemed a little upscale, a vestige from an era when one needed a lift up into a carriage, but I remember it from our Christmas visits to my father’s home in Montclair, NJ, when we did not need it to ascend into our Volare station wagon. It sat on the front corner of the driveway. After Daddy’s parents died, the stone moved to our house in Haverford, set at the end of the stone path that led to a patio in our home on Orchard Lane.

Here is what I remember about my dad and that stone:

It was October, still warm enough to walk barefoot on the bricks terrace in front of the front door. Those held the warmth in the way that the darker stones on the side patio did not; those were cold, damp, slippery with moss, but the bricks were warm. I could smell dirt; no doubt, my mother had been doing something out front, pulling up pachysandra, planting bulbs, clipping. An earthy, rooty smell clung to the smoky air—leaves burning in a wire basket at the end of the driveway. I’d come down looking for her, pushing out the open screen door, expecting to find her out front or in the garden at the side of the house, box bushes ready to be draped with burlap before winter. No Mom. I heard an odd noise, raspy, unfamiliar. First, I thought it was the desperate caw of a lost crow. But, around the side of the house, by the carriage stone, I saw my dad, sobbing.

“Daddy?” I asked, tentative. I had rarely seen him so unguarded.

“Bugs,” he said, taking a handkerchief from his pocket and blowing his nose.

“Not Bugs,” I clarified. “Ann.” Bugs was his love-name for my older sister.

“Ba’nan,” he corrected. I stood a distance from him, my tall dad somehow shrunken.

“You’re crying,” I announced without a lot of warmth or interest. Crying was our default these days. I cried plenty. I knew perfectly well why he was crying, but there wasn’t any room in my own sorrow for his.

“It’s hard, Ba’nan. He was the last to carry my name.”

I bristled. “I’m a Klotz, too, Dad. I have your last name.” My heart was as hard as the rock that held my father’s gaze. I was angry, a good cover for broken.

“You are, Ba’nan. But, you’re a girl. When you marry, you’ll have another name.”

“No, I won’t,” I spat, though, until this moment, I had looked forward to losing Blood Clots as a nickname. “No, I won’t. I’ll always be a Klotz. I’m a feminist.”

“You can count on me, Dad, I churned silently. I won’t die. I won’t change my name. I’ll be here.” But not really. I kept my name, but I hardened my heart. I moved away. There was room for my grief, for my mom’s, for my sister’s, even. But no room for my dad’s. I could not take care of him, too. He would have to take care of himself. Thankfully, my sister loved him hugely, cared for him with devotion until the end of his life, went to Phillies games with him, packed him up from one nursing home and found a bed in another, put up with his outrageousness and never faltered. The good daughter.

And a few years before she asked about the stone, she had phoned me in December.

“I think you’d better come,” she said gently. “He’s pretty bad. He isn’t waking up. We think it will be soon.”

So, full grown now, I flew from Cleveland to Philadelphia, renting a car, using one of those pre-Google map devices to get me to his final nursing home. Kind nurses signed me in, showed me upstairs, quietly opened the door to his room.

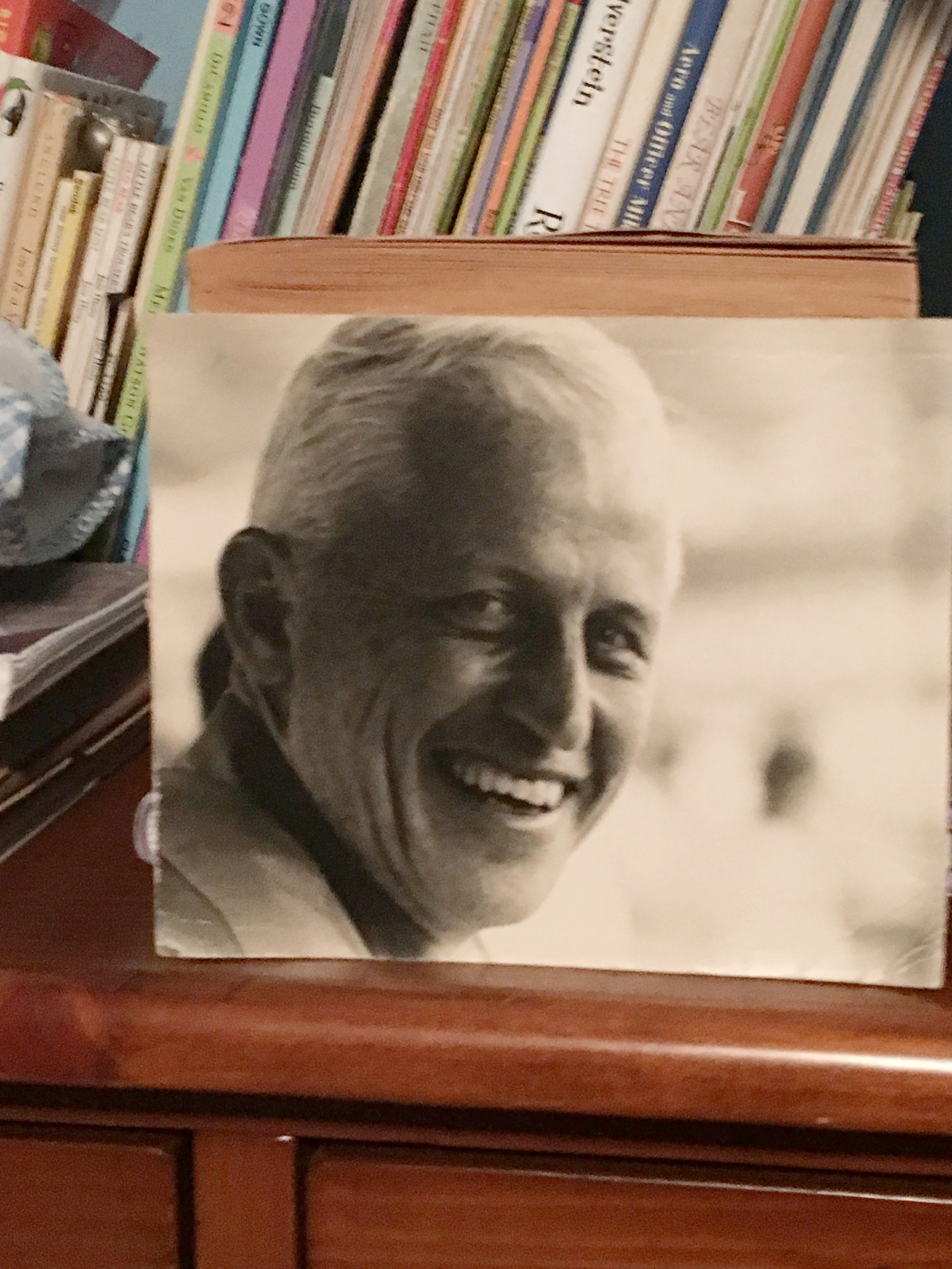

He was in bed, so much smaller than I remembered him, eyes closed, hair mussed, which it never was in real life, unshaven. My dapper dad enfeebled.

“Bugs,” he said—my sister’s name again; I felt my irritation rise, suppressed it.

“No, Daddy, it’s Ann.”

“Ann? You can’t be here. You’re in Ohio.” He struggled to sit up to see me.

“Well, Daddy, the reports on you weren’t so good in Ohio, so I came to see for myself.”

“I’m fine. Better than your mother,” he exclaimed, competitive to the last.

I laughed and pulled up a chair to his bed and we spent the morning telling stories.

The nurse came in, amazed to see my dad so lively.

My dad, man of mystery. It was the summer of 1977, and my mom and I had just bought a red plaid midi-kilt in a shop in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“You’ll have it forever,” Mom declared, and she was right. I still have it.

We walked towards Harvard and Radcliffe, this college tour of the East Coast that I was trapped on with my parents. Wellesley, Tufts, now Harvard. Mostly I was thinking about how I wanted to get home so I didn’t miss Doug’s party before he left for Kenyon. We were crossing Harvard Yard when my dad pointed, “That’s where I lived.”

I dropped back to Mom, trailing a few steps behind.

“I thought Daddy went to Penn,” I hissed, puzzled.

“After he flunked out of Harvard.”

Who knew? How could this part have been left out? What other secrets did he have?

My father had been a supply sergeant during the war; afterwards, at Penn, rescued from his Harvard ignominy, he was a jock, playing lacrosse and rowing crew. He loved his fraternity—St. A’s--and being part of a group. He was the dapper, debonair older man who met my mother at her debutante party and wooed her. They were married for 36 years and divorced for 25. My dad struggled to hold a traditional job; he wanted to be a schoolteacher, but his father didn’t think that was high-status enough. He worked briefly for a bank, flirted with law school, was self-employed as a manufacturer’s representative much of his professional life. Mother said she always knew when he appeared down the lane in the middle of the day that he had been fired again. A personality test he took in college suggested he would have been happiest as a forest ranger.

As a little girl, I was afraid of him when he shaved and lonesome when he took me to baseball games because he had to have his earphones in to hear the game, so he couldn’t answer my questions. But some of my happiest memories are of reading with him in the big chair in the living room—Our Island Story was the name of the volume. I was thrilled by Bodaecia, by the little princes in the tower, by Henry the Eighth and his wives, by Mary, Queen of Scots—no professor in college held a candle to my father’s ability to tell the story of British History.

When I read Death of a Salesman at 17, I felt a frisson of recognition; my dad was liked, but he wasn’t well-liked. I had seen a tightness in people’s greetings at the Club out for dinner—I knew people were polite, but not everybody really liked him. He never quite found his place.

I spent much of my adolescence hating him because he humiliated my mother over and over again. A ladies’ man, he flirted and more—repeatedly—liaisons poorly disguised. After he retired, he gave himself over entirely to sports—playing tennis and golf, teaching tennis to kids, traveling the world to attend tennis clinics or play golf on other courses…only as an adult did I realize what an odd path he took. But it was through teaching that I found my way to him again—teaching helped us build the bridge to meet each other.

In 2004, he came to Cleveland to see me installed as the Head of Laurel. A former Laurel headmaster had been Daddy’s teacher at prep school—he loved that connection. I was happy to have him with me. Because after I had been married for a long time, I began to understand that it takes two to make a marriage cool. Perhaps my father wasn’t entirely the villain I had made him out to be. And I began to do the work of coming to know him all over again, of listening more closely to his story.

Daddy was chronically late. Every short cut he insisted on taking got us more lost. He kept Archway cookies under the front seat of his car. He loved to fly fish and play golf and tennis. He loved cross word puzzles and ceremonies. Once, I moved away from home, Daddy cut out articles and sent them to me—Ann Landers columns, anything about Katherine Hepburn or Princess Diana, editorials about education, reviews of books or plays. He never gave up on me, even though I was so hard on him.

When our son, Atticus, was a tiny baby, Daddy visited and remarked that he never knew babies were born with eyebrows—I shook my head—he had had three children and seven grandchildren! But infants were never on his radar. He was delighted we had passed his middle name, MacPherson, down on to our baby son, but I almost fell off the rocking chair that summer afternoon when I learned that my dad was no more Scottish than anyone you might meet on the street. In 1920, he had been named for his father, and his father for his own father, who had been named, curiously, for the Mayor of Newark. That mayor employed my father’s great-grandfather as an engineer to design a water reservoir system in Newark—a crazy scheme in the 1850’s, but the mayor was forward-thinking, and the reservoir system is still in use today. In gratitude, my great-grandfather named his son for John MacPherson, the mayor, and the name has come down through the generations. I shook my head and laughed—another secret spilling from my father’s lips. Of course, I had never asked, had just assumed his Scottish heritage.

On that wintry afternoon by Daddy’s bedside, we talked about school. I thanked him for being my dad, for giving me my love of poetry and literature, for being proud of me. Occasionally, he wandered into a past where I could not follow—he told me all about a date he had had with a pretty girl in the 1930’s. My father loved pretty women. Eventually, he fell asleep, and though I sat by his bed for several more hours, knitting and thinking about the stories of my childhood, he didn’t wake again. A few weeks later, he slipped away, more dignified in death than the colorful escapades that characterized his life would have predicted.

So, yes, some years ago, I accepted my sister’s offer. I set the stone at a jaunty angle in front of our house in Eagles Mere, near the snowball bushes. I wish I had been kinder to my dad long ago; it takes a long time for adamantine rage to melt. But I bear the name on that stone, my father’s name, now with more pride than anger. That hard heart of mine has released its clutched fist, softened, found a way to forgive a man who was, alone, crying, for his lost son.